SIT’s Writing Guide

25/11/2019Cyber security is a tough sell. Millions of dollars have been spent promoting the need for anti-virus yet the technology was arguably redundant by the time it became a widely-recognised necessity.

Two-factor authentication, the most critical user account security tool, has had a decade’s support from the largest technology companies in the world yet Google, its biggest backer, says less than 10 percent of its customers use it.

Awareness (influence) practitioners face the same challenges in selling cyber security as do tech giants in plugging two-factor authentication. Their product, cyber security, is to many people abstract and onerous, and to others, simply boring.

But it is anything but boring. In journalism, a story leads if it bleeds, and cyber security’s criminal underground, clandestine nation-state spies, and anarchic hacktivists proffer plenty of digital blood.

The theory is easily tested; the average punter in the average pub will mutter something of hooded hackers if asked about Russia’s election meddling, yet they will glaze over if you inquire about two-factor authentication.

These bleeding stories are lubricant for otherwise dry but important cyber security messages.

It is the awareness practitioner’s job to find and deploy these stories as a tool to win hearts and minds.

Writing ruthless

Skilful writing comes with practice, not literacy. Anyone who wishes to be a competent writer must treat their craft as a professional skill to be honed over years and across thousands of words.

Stephen King was right when he said good writers must above all else “read a lot and write a lot” adding there was “no way around these two things” (On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft).

Writers can learn from any form of professional writing; established mastheads like the BBC through to tabloids and trash mags, classics, and best-seller fiction. They should read breaking news from established mastheads as a daily ritual, but also vary their diet with long features, opinions, and any other professional form or source they like.

Most casual blogs should not be considered a source of writing techniques.

Professional written sources serve as a guide for writers where reading rules prove difficult or simply onerous.

If reading is easy, writing is hell. Budding and established writers must have thick tanned hides that absorb criticism easily. They must be prepared to watch their treasured prose flayed by more experienced hands, or by the knowing voice in the back of their heads, and be open to continually shed and evolve their writing techniques for the sake of improvement.

They should acknowledge the process of becoming a good writer will likely take years.

Novice writers should be absent of fixed ideas on what techniques make good writing.

This combination of professionalism – writing in the style of a trained writer rather than a casual blogger – and ruthless editing are pillars on which good writers stand.

Writing hard

Awareness professionals new to writing should follow the style of hard news. Doing so offers the writer a repeatable and methodical process and the reader a familiar form.

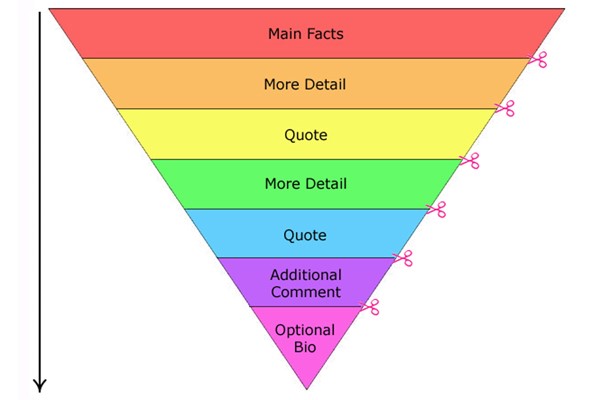

The process is represented in the inverted pyramid. In this ‘first news first’ model, the most critical information is captured in the headline, standfirst (a short sentence underneath the headline), and lede (first paragraph), while each subsequent paragraph provides the reader with context to better understand the story.

Information that does not directly answer who, what, when, why, and how is discarded from the opening paragraphs.

Modern online headlines have departed from their classic newspaper form (facts stated in about five words or less) and are regularly much longer and cater to evolving consumer trends and masthead schtick with the inclusion of pop culture references, memes, and posited questions.

Hard news form allows the reader to exit the story early without missing critical information. It has served journalists for 140 years since its birth at the turn of the 20th Century (The Evolution of the News Lead Errico et al., 2017) helping them to more quickly inform their readers.

Adhering to the hard news style and avoiding flowery prose, casual writing, and cliché takes sustained discipline, but over time equips the writer with the knowledge to write fast and well, and to identify good stories.

Opening ledes for features, special reports, opinion pieces, and blogs can start at a different spot from hard news and may kick off at some point deep in the story, perhaps amid conflict or tribulation.

These colourful ledes are more difficult to write than many budding writers suspect and are easy to mess up. When well executed, rich openings immerse the reader deep in a story. Writers can create themes in these openings which they can return to throughout their story.

Writing blocked

Stories are often difficult to start. Writers find themselves unsure if their story will attract readers, or how to begin telling it.

Reading widely helps build a nose for news in the budding writer. Ideas for hard news and features come from reading those forms.

Newly disclosed security breaches, exploits, vulnerabilities, and allegations of nation-state hacking are reliable hard news topics.

Story ideas are not all about hard news. Advice that helps readers protect themselves, their friends, and family, and stories that entertain and enamour readers to cyber security are fantastic news ideas.

Technical pieces on, for example, new security upgrades for popular cloud services or tools and techniques to more quickly pass cyber security checks help IT readers save or make a buck.

These stories can open ‘softer’ than current event hard news but should still answer the same questions demanded by the inverted pyramid of answer who, what, when, why, and how.

Writing for readers

Each piece of writing is written for specific audiences (although novelist King says ‘write for yourself’). There is no such thing as ‘everyone’ in terms of readerships; even daily newspapers who can be read by anyone are written with archetypal readers in mind (You are what you read? Duffy, Rowden, 2005)

Writers should attempt to identify their readers’ interests, subject knowledge, and tone before writing a piece, and adjust their technical complexity, assumed knowledge, and use of jargon to suit.

Writing message

While there is little evidence that attention spans are constrained to minutes or seconds, or are indeed diminishing (Attention span during lectures: 8 seconds, 10 minutes, or more? Bradbury, 2016), writers are likely to lose their readers if they confuse them with jargon, absent context, or excessive information.

Good writers respect their readers’ time and provide them with adequate context such that they can comprehend and therefore care about the written subject, without being laden with information; Long documents can turn readers off a story.

Ruthless editing to remove details and leave behind important, reader-relevant facts helps clarify messages. In much hard news writing, less is more.

Writing refined

It is difficult for writers to edit their own draft work since they are too familiar with and often wedded to their narrative. A second pair of eyes, whether experienced in writing or not, paired with the earlier concept of ruthlessness goes far to help overcome this.

Those editing should be able to understand the story without being additionally briefed.

Editing is done throughout a story. Writers may spend considerable time rewriting sentences for a more complete draft or may pick up the effort on a second or third read through of the story.

It is generally more effective to refine a story during the initial writing process (Empirical studies on text quality and writing processes, Tillema, 2012) and may also help to maintain story structure.

Writing exquisite

Grammar is the signposts and traffic lights that guide readers through a story. It tells them when to take a breath and when to consider ideas related or distinct. Poor grammar can confuse an otherwise brilliant story.

Learning grammar and its many mutable and timeless rules is tough but critical. Writers should commit to mastery over a period of time such that it is never a chore but rather an obvious benefit which allows them to express their ideas with speed and clarity.

A guide to hard news

Keep in mind:

- Subject-verb-object: Andy ate cereal.

- Keep vocabulary simple. Never use a complex or uncommon word when a simple common word will suffice. Words must be specific, emphatic, and concise.

- Each sentence must be clearly understood at a glance by your reader, on first reading. Its meaning must be unmistakable.

- Don’t repeat words in a sentence, other than conjunctions and, but, if, a and so on. Don’t use security twice for instance.

- Make your sentences active, not passive. This makes them clearer and shorter.

The victims lost money to the banking trojan. (passive).

The banking trojan stole victims money (active).

- When ideas are complex to your reader, as dark markets are, use similes and metaphors that readers will be familiar with. Dark markets have the look and feel of ebay.

- Don’t ever use clichés as these phrases carry little meaning: only time will tell does not say when the thing will happen. Be specific. The effectiveness of police efforts against dark markets is unknown.

- Maintain your tense. If you use they, and staff, don’t switch to you. If you use says don’t switch to said.

- Always use says or said, never stated, believed, exclaimed.

- Never use exclamation marks. If someone yelled at a protest, explain in writing that they were yelling.

- One idea per sentence, and almost always one sentence per paragraph. Two sentences in one paragraph is okay if they are so closely related that they would otherwise be one sentence.

Structure

News writing is formulaic and repeated. The style has not changed since 1845. It crosses languages and cultures.

It is like changing tyres on a car: Jack raised, nuts off, tyre off, nuts on, jack lowered. The car may change, but the process remains the same.

Deviating from the structure is fraught.

Opening paragraph – lede

Engage the reader instantly. Summarise what the story is about in less than 40 words. Cherry pick what you see as the few most attention-grabbing and relevant facts, points of contention or interest in the story.

Answer where possible each of these questions in the opening par: who, what, when, where, why. The shorter the lede is the better (tabloid is super punchy at less than 25 words), but it must answer those questions.

Examples from this ABC news story.

Lede: Former NSW Labor minister (where) Ian Macdonald (who) has (when – implies today) been sentenced to 10 years’ jail (what) over the decision to grant a mining licence to a company run by former union boss John Maitland (why), who will spend at least four years behind bars.

Second paragraph

This supports the lede. Here you add additional facts that did not make the cut for the lede. It often answers the how that is missing from the lede.

It may have essential background context for a topic that is foreign to the reader, or if the reader has knowledge of the topic, then it may include more who, what, when, where, and why.

In March (when), Macdonald was found guilty of misconduct in a public office (what).

Third paragraph

In hard news writing you will introduce the expert (talent) in the story. This may be a security research who has discovered something or is warning of a threat.

Use this structure [Company –title – name] says [the most important fact – often you repeat part of the lede].

Eg: NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian said the cases of disgraced ministers Mr Macdonald and Eddie Obeid demonstrate some of the darkest years of the Labor government.

“We don’t ever want to see that return to New South Wales,” she said.

Fourth – fifth – (sometimes sixth) paragraph

Here you write your talent’s quote (grab). Don’t force three grabs if the third repeats the other two or is weak. Even one is okay if you don’t have two strong grabs.

“I think the public will feel very well served that he [Mr Macdonald] is behind bars as he should be.

“Any elected representative who does that wrongly by the people of the state deserves the book thrown at them.”

Remaining paragraphs

Fill out the story in decending order of importance. Give background to the story.

Did some other talent in a blog weigh in? Google the subject. You’ll find news stories, blogs, and other sources. Cite those here. You can introduce that talent in the same way as above, but generally with less grabs. Quote them once perhaps.

End it when it fizzes. Don’t waste time giving too much history because few readers make it this far. However, technical audiences have amazing attention spans and will almost always read to the end.

If it’s not hard news?

Stick to hard news when starting off. It is formulaic and repeatable.

Hard news is new, timely content. For journalists it is that day, or it was previously unknown to the public.

It is war, car crashes, politics, and robberies.

For cyber security writers, it is malware campaigns, victims being scammed, data breaches, software vulnerabilities and exploits.